Mary Turberville (1623 – 1702) came from a large and ancient Dorset/Somerset family, the Turbervilles, whose ancestor had accompanied William the Conqueror. Thomas Hardy later based ‘Tess of the D’Urbervilles’ on this family. Mary’s brother Daubeney was a noted oculist.1 We know that Mary assisted her brother throughout his medical practice, working with him in London and Salisbury, and that she herself was a skilled and experienced practitioner.

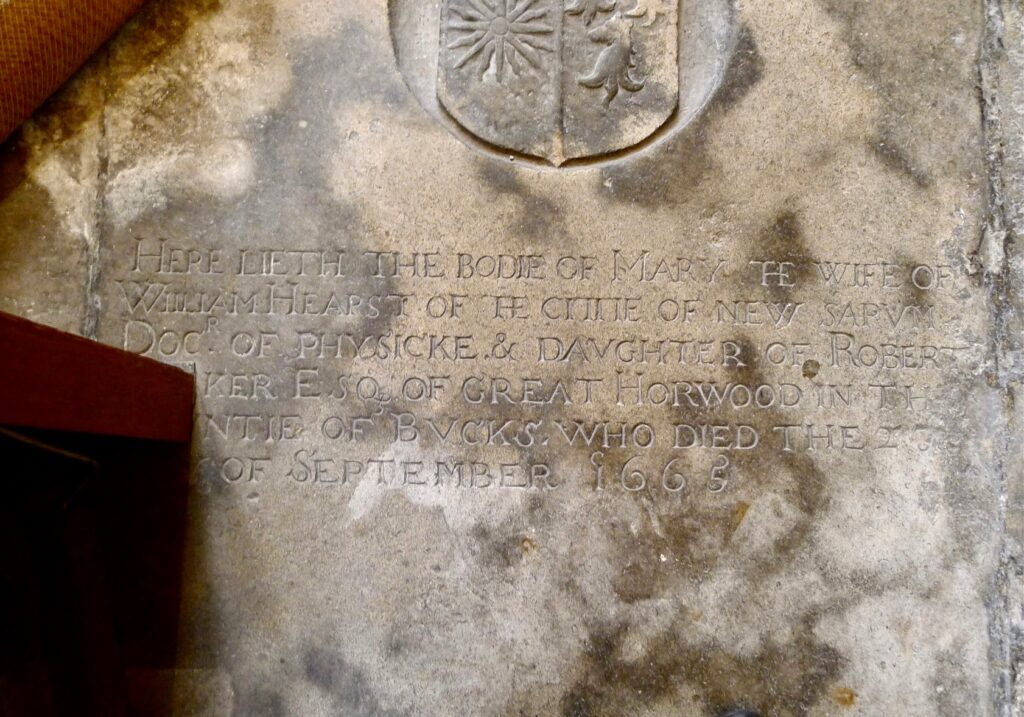

Mary also played a pivotal role in one of Salisbury’s most famous ghost stories about an incident that occurred in June 1666 at no.17 of the Cathedral Close. It was the time of the Great Plague and Charles II had fled London, staying briefly in Salisbury before moving to Oxford. The air was full of rumours and superstitions; a good ghost story would have had its place. No.17 had previously been occupied by William Hearst and his family who had moved out following the death of William’s wife in September 1665.

Soon after they moved in, Mary reported seeing ‘a ghostly lady’ claiming to be a ‘wronged first wife.’ The apparition told her that a document hidden behind the wainscot2 in this house would prove this, and Mary did indeed find such a document. We are told that Mary, on discovering the document, took it round to William Hearst, still living in Salisbury, and demanded justice for his first wife’s children. After initially denying everything, Hearst then admitted that a wrong had been done and set about putting it right. Salisbury historian John Chandler suggests that this is the ‘best fit’ of all the available facts and that she had invented the ghost story to save the reputation of William Hearst; later she embellished the story to include ‘celestial singing, blue swirling smoke and angelic voices.’ The story demonstrates that Mary was a clever detective, a sensitive person and not afraid to challenge a perceived wrong.

Daubeney died in 1696, aged 84, his will naming Mary as ‘of the city of London’, so by then Mary must have resumed her London life and practice, taking with her the treatments and recipes her brother had used: evidently her practice thrived. It was rare though not unknown for women at this time to practise such professions in their own right. She died in 1702, a wealthy woman, the year Queen Anne ascended the throne. After bequests she left the residue of her estate to her ‘dear friend’, Catherine Eller.

Notes

1 An oculist is a former term for an eye doctor; that is a specialist in treating eye diseases. In modern times the closest to this would probably be an ophthalmologist. Dr Daubeney Turberville was an eminent oculist, counting Robert Boyle, Samuel Pepys and even the future Queen Anne among his patients. He is also known for first writing about cases of colour blindness in the academic journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, in 1684. He is commemorated in Salisbury Cathedral.

2 A wainscot is an area of wooden panelling that can be found on walls.

Written and researched by Beatrice King, edits by Anne Trevett, notes by S.Ali.

We would like to thank Salisbury Cathedral for the photographs of Mary Hearst’s memorial stone in the Cathedral.

We would also like to thank Celia Cotton for assistance with finding sources for this profile.

Sources:

Chandler, J, 2009, The Reflection in the Pond – A moonraking approach to history, Hobnob Press pp. 23-39.

Howells, J & Newman, R, 2014, Women in Salisbury Cathedral Close, Sarum Studies no.5, pp.24-6.

James, RR, 1926, Turberville of Salisbury, British Journal of Ophthalmology, Series 18, 10(9), pp. 465-74.

Dictionary of National Biography see: Daubeney Turberville https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-27823

Burial records St Andrews, Holborn, London, 1702.

Wills of Mary Turberville and Daubeney Turberville.