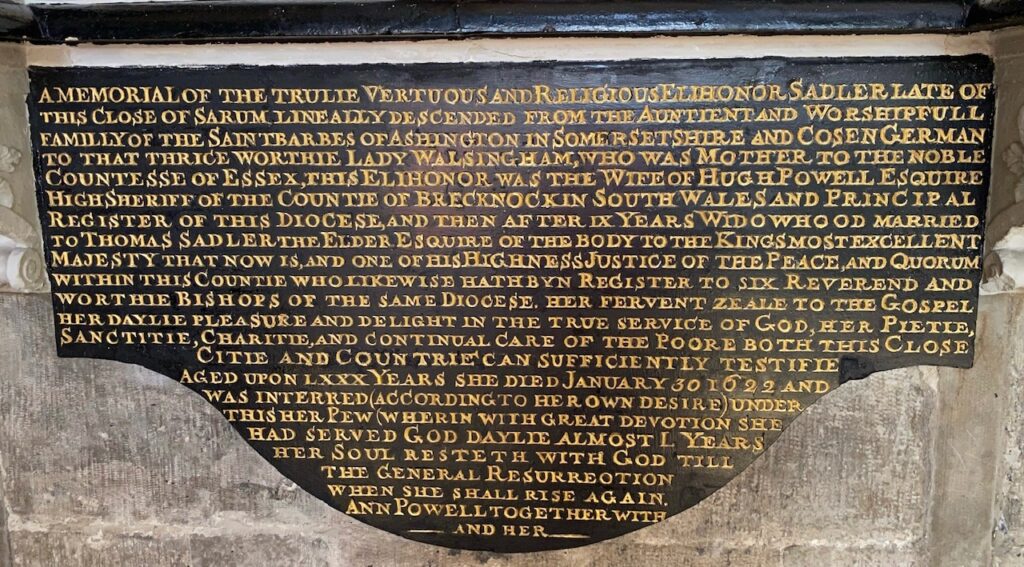

Visitors to Salisbury Cathedral may notice the striking monument to Elihonor Sadler, and some may know of her part in the story of the King’s House in the Close, which is now houses the Salisbury Museum.1 The details of Elihonor’s life may be sparse but give us a window directly into a period that is at the heart of English history and the story of our city. Through the different aspects of her life, she leads us directly to the upheavals of 16th and early 17th centuries in religion, politics and social welfare.

Religious upheaval and the establishment of a new order: born in the last years of Henry VIII’s reign, Elihonor’s childhood was characterised by enormous swings from the extreme Protestantism of Edward VI to the equally extreme Catholicism of Mary. In Elizabeth’s reign English post-Protestantism gradually emerged in the more moderate form of Anglicanism. Salisbury was at the centre of this, for this was largely due to the works of John Jewel, Bishop of Salisbury 1560-71, whose seminal work, ‘Apologia’ laid these foundations. However his arguments were hotly disputed by his Canon treasurer, Thomas Harding. From her monument we know that Elihonor had her own seat in the Cathedral from where she worshipped daily for almost 50 years. Jewel worked hard to improve standards of preaching and pastoral care in the diocese, so we can assume this was reflected in cathedral worship at this time in which she shared.

Political upheaval: Elihonor was from the ancient family called the Saint Barbes, and Elihonor’s first cousin, Ursula St Barbe, was the second wife of Sir Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth’s chief spymaster, so we are led thereby into the murky world of Elizabethan politics and espionage. Elihonor married twice, firstly to Hugh Powell (d. 1587), High Sheriff of the County of Brecknock in South Wales, and secondly to Thomas Sadler (d.1643), Registrar to Bishops of Sarum, in 1596; she was then 53, he was 35. She did not have any children.

Social welfare changes: According to her monument, Elihonor was very generous in her charitable giving. She lived through the passing of one of the most important Acts designed to care for the poor and destitute, necessitated by the dissolution of the monasteries some 60 years earlier that had hitherto provided such care. The Elizabethan Poor Law Act of 1601 placed the responsibility of care on to each parish. Elihonor’s first husband left her the income from his properties in Fisherton Anger, provided she made no claim whatsoever on his manorial estates in Wales (presumably to keep them in the Powell family). This enabled her to continue her generous giving, though no direct record of this survives and she left no will. Thomas Sadler, however, was very different. Even ten years after her death his own will shows him to be still in awe of her benevolence, and his own generous bequests to the poor were explicitly inspired by her example.

Note

1 In the 17th Century, King James I was entertained here, and the building became known as the King’s House.

Written and researched by Beatrice King. Edited by Anne Trevett.

We would like to thank Celia Cotton and Ruth Newman for help with finding sources.

Sources and further reading

Howells, J, and Newman, R, 2014, Women in Salisbury Cathedral Close. Sarum Studies no.5.19-20

Wills of Hugh Powell & Thomas Sadler (1634)

Bishop John Jewel ,1565, Apologia (in Latin, also available in translation)

Saint Barbe genealogy – Ancestry, accessed February 2021