Joan Popley was a benefactress who donated 20 messuages (residential buildings) in 1570, in Basinghall Street, London, ‘for the relief of the poor of Salisbury’. Joan Popley was married to Thomas Popley, a merchant, property-owner, member of the corporation of Salisbury and alderman of the Market Ward in 1564. There is very little publicly available information about Joan Popley herself, but a portrait of her was painted by the artist Robert Peake the elder.

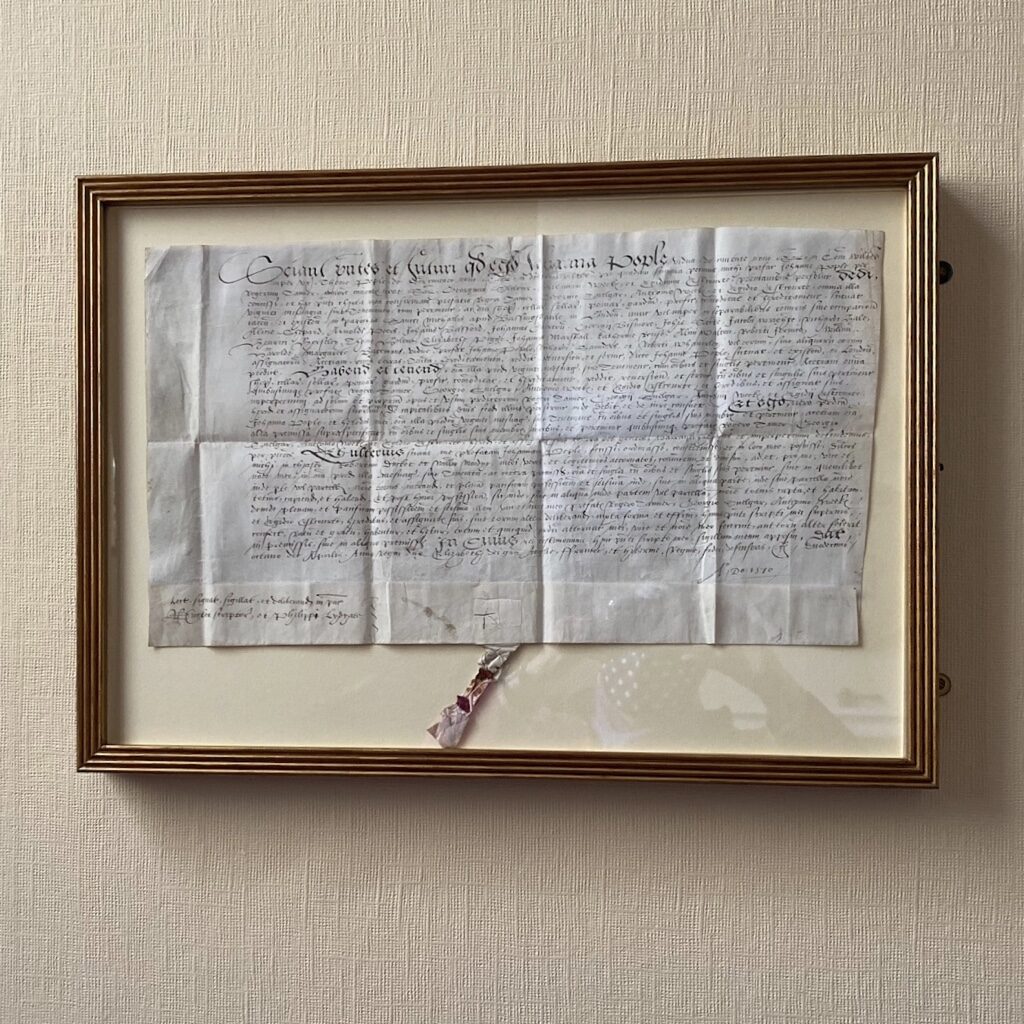

The property that Joan Popley gifted has undergone many changes over the years1, however the income it generated was used to support the poor and needy in several ways over the centuries in line with the legal and social context of the time2. This support included providing money for the poor, helping to fund a workhouse, providing an allowance for Brickett’s hospital, financially supporting widows, and helping to rebuild Eyre’s hospital. The charity’s income was also used to help other charities when needed. Today the charity is linked with the Salisbury City Almshouse and Welfare Charities3. You can read at translation of her bequest Joan Popley – Deed Translation here.

Notes

1In 1666 the houses burned down in the Great Fire of London. They were rebuilt in 1768.

An extra house was bought in 1806. The houses were sold in 1955 and 1956.

2Joan Popley’s gift was intended for the relief of the poor. However it is important to note the national social and political context of the period, and how the poor and disabled were treated at the time, influencing a number of legislative changes which became known as the ‘Poor Laws’, which detailed how the poor and needy should be financially supported and provided for. The legislation was influenced by several social, economic and population-related factors such as epidemics, population changes, reduction in workforce, and social attitudes toward the poor at the time. This is a brief overview, but we encourage you to read further into the topic; we have provided further reading in the ‘Further Resources’ section below.

During Joan Popley’s time, societal shifts in relation to the poor were already underway in England. These had started approximately four decades earlier with the Vagabonds Act of 1530, leading to a number of changes in legislation which changed the way that the poor would be treated and/ or provided for. It is argued that the poor laws passed during this time, which also formalised arrangements for the poor to be financially supported and given accommodation, were the precursor to the modern-day welfare state. Some of these laws meant that the poor were cared for, but others meant that they were set to work, and many were mistreated and subjected to violence. This also depended to what extent they were perceived or categorised as ‘deserving’ poor, whether they were deemed as able to work to support themselves, and whether they were seen as ‘idle’ or unwilling to work.

By 1570, when Joan Popley donated her properties, poverty was increasing in England on a large scale. Under the 1572 Vagabonds Act, a Justice of the Peace was appointed in each Parish and given the responsibility of registering the names of all the poor and unwell people and distributing relief to those in need. They could also license some people to beg if the Parish was unable to provide for them. A national poor law tax was introduced to raise money to help support the poor. As a result of the Poor Act 1575, parishes had to provide materials (e.g. wool, hemp, flax and iron) for the poor to work on. Houses of correction were established where the poor were made to work and punished if they did not. In 1597, the Act for the Relief of the Poor led to ‘Overseers of the Poor’ being brought in to help people find work, collect the poor rate, distribute the poor rate to those in need, and supervise the poorhouse. A major change occurred with the Act for the Relief of the Poor 1601 (also known as the Elizabethan Poor Law and the Old Poor Law) which brought in a poor rate. This was a tax on property which was used to provide relief to the poor. Although this poor rate brought in more money, it was still not enough to support the increasing number of people in need. In 1602 a workhouse was established in St Thomas’ churchyard and some records show that it was financially supported from the rent of Joan Popley’s properties.

The poor law system continued in the context of historical events and social changes 16th and 17th centuries such as the plague epidemic, famine, and rising costs of grain. In Salisbury, such changes led to mass unemployment and economic crises which led to many people going hungry. The proportion of poor made up quite a substantial amount of the population. The rental income from Joan Popley’s properties continued to be used for the poor and for supporting hospitals. A number of other charities were also operating in Salisbury at the time. In the 1620s a new group of Puritan councillors wished to reform the city and ‘eradicate the sin of idleness’. They invested in schemes to raise income and set the poor to work, such as a municipal brewery, an updated workhouse, and a storehouse (where the poor could exchange tokens for food and essentials). They also set up a scheme to employ poor children to work in the workhouse and in the town for masters. The rental income from Joan Popley’s properties continued to help cover the costs of the workhouse. However these schemes did not succeed due to a number of factors including political opposition, lack of profitability from the brewhouse, and a lack of willingness to employ children. By the 1640s the Brewery and storehouse had been closed down as they were not sustainable.

In the 18th century workhouses were established across the country and the Speenhamland system was brought in to supplement the wages of the rural poor. During this time the income from Joan Popley’s properties were being used to provide funding for Brickett’s hospital, the Salisbury workhouse, and for the relief of the poor. The income was also used to assist other charities when needed.

In early 19th century England there was large-scale social unrest, war, and mass unemployment. The price of grain increased but was not accompanied by wage increases, which led many agricultural workers into poverty. In Salisbury the locals were also concerned about the increasing numbers of people begging on the streets. In 1818, lodging houses were set up in Culver Street and St Ann Street where beggars could have food and accommodation for one night. During the 1830s Joan Popley’s properties were still generating income, and this was used to support widows, and to give allowances to the poor and almspeople. The income also supported Eyre’s Almshouse.

Around this time there was widespread concern about the cost of helping the poor, when taking into account the rising costs of bread, and the increasing population. In addition, the wealthier people felt that they did not want to pay for poor people who they believed to be ‘lazy’. There was rising pressure for the government to reform the system. This change finally arrived in the form of the Poor Law Amendment Act (1834); known as the New Poor Law – a complete overhaul of the poor relief system. Parishes were grouped together into ‘unions’ which had to work together to build workhouses if they did not already have them. Assistance could only be obtained via working in a workhouse, and the conditions of the workhouses were deliberately terrible to deter people from applying for help unless they were desperate. There were a number of objections and protests, and people feared having to be sent to work in the workhouse, because essentially this meant being punished for being poor and/ or unable to work.

Due to widespread opposition and scandals (such as the Andover workhouse scandal of the 1840s), further changes were made including an introduction of a Poor Law Commission, followed by the Poor Law Board which had greater scrutiny over the poor law system. By the late 1840s people in workhouses were mainly ‘incapable, elderly and sick’ (Fowler, 2014, p. 73).

By the late 19th century the poor law system had fallen into decline with less people on poor relief. Around this time (in the early 1870s) Joan Popley’s charity was consolidated with other charities in the area and money raised was was used to rebuild Eyre’s hospital. The money from Joan Popley’s charity was also used to support Bee’s charity. In the early 20th century, further changes were made to the poor law system, with the introduction of the welfare state. There were also many further sources of assistance becoming available for those in need. Eventually all poor law legislation was abolished in 1948 with the National Assistance Act.

3To this day, the charity continues to be listed as a registered charity and is linked with the Salisbury City Almshouse and Welfare Charities which help residents in Salisbury who are in need, providing assistance such as grants, facilities and accommodation.

Sources

Alexandra Briscoe (2011). Poverty in Elizabethan England. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/tudors/poverty_01.shtml

Peter Clark and Paul Slack (Eds). (1972). Crisis and Order in English Towns 1500-1700. Routledge.

House of Commons. (1861). Parliamentary Papers, Volume 21, Part 6. H.M Stationery Office.

Elizabeth Critall (Ed). (1962). A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 6, pages 105-113 and 168-178. Originally published by Victoria County History. Digitised version available at: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol6

Simon Fowler (2014) The Workhouse: The People, the Places, The Life Behind Doors. Pen and Sword Books.

National Archives (n.d.) 1834 Poor Law. Lesson at a glance. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/1834-poor-law/

Salisbury Local History Group (2000) Caring: a short history of Salisbury City Almshouse and Other charities from 14th to 20th Centuries. Salisbury City Almshouses and Welfare Charities.

Paul Slack (Ed). (1975). Poverty in Early Stuart Salisbury. Wiltshire Record Society. Warwick Printing Company Ltd.

Further reading:

There are a number of websites detailing the poor laws and we encourage you to read a wide range of them, in order to get a broad perspective of what happened at the time.

A very simple and accessible summary of the Poor Laws can be found here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zxjgqty/revision/3

Wikipedia entry on Tudor Poor Laws: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tudor_Poor_Laws

UK Parliament website on Poor Law reform:

British History Online: Parish Government and Poor relief

https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol4/pp342-350

National Archives: 1834 Poor Law lesson at a glance:

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/1834-poor-law/

Paul Slack has written extensively about the 16th and 17th centuries and some of his books are listed here.

Paul Slack (1990) The English Poor Law, 1531-1782. The Economic History Society. Macmillan Press.

Paul Slack (Ed). 1975. Poverty in Early Stuart Salisbury. Wiltshire Record Society. Warwick Printing Company Ltd.

Thank you to the Salisbury City Almshouse and Welfare charities for their help and to Salisbury City Council for permission to use the picture of Joan Popley. map shows the location of Brickett’s Almshouses