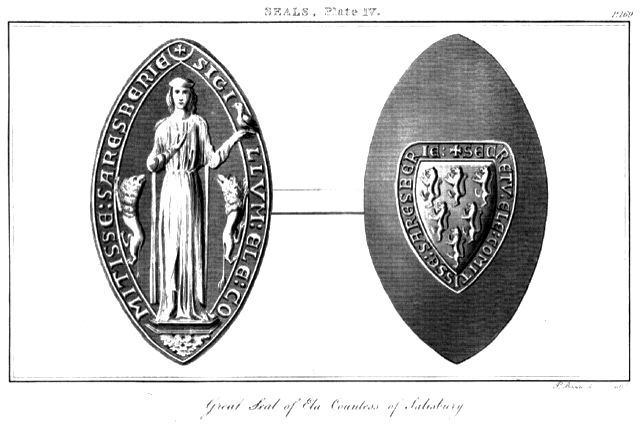

Ela Fitzpatrick (D’Evreux)– Countess of Salisbury (1187-1261).

In an age where women rarely had the power to make a significant contribution to the community1, Ela Fitzpatrick (D’Evreux), 3rd Countess of Salisbury, was instrumental to the creation of significant institutions in the region. She has been referred to as a ‘towering female figure’ and left an important legacy that lives on even today, over 800 years later.

Born in Amesbury in 1187, Ela was the only child of William Fitzpatrick and Eléonore de Vitré. After her father died, returning from the Crusades2, there is confusion about the remainder of her childhood. It is known that she was made a royal ward3 at the age of nine and taken to Normandy, France, in mysterious circumstances, perhaps on the actions of her uncle who wished to claim her father’s wealth and titles. However, she was located and freed by the knight William Talbot. Legend states that he located her by singing under all the castles in the area until she signalled her presence

Upon her return to England, Ela was betrothed and then married to William Longespée, who was the illegitimate son of King Henry II. In 1220, Ela and William laid foundation stones for the new Salisbury Cathedral after the decision was made to relocate from Old Sarum4. It appears that their union was happy and bore at least four sons and four daughters. Significantly, Ela demonstrated her enduring commitment to her husband by never remarrying when he was feared lost in battle, or after his death in 1226. This was highly unusual at this time and was only possible as there had been a change in the legal rights of women in the eighth clause of the Magna Carta,5 which meant they were no longer obliged to remarry. More cynically it has also been pointed out by some historians that this ensured that the title of Earl was reserved for Ela’s eldest son, William II Longespée, and not passed to a new spouse.

After her husband’s death, Ela held the post of Sheriff of Wiltshire for two years. Ela also founded the Abbey of Lacock in Wiltshire and established Hinton Priory6. Ela remained implicated in the development and life of the convent of Lacock; negotiating many rights and privileges to ensure it could be self-sufficient. She became Abbess in 1241 for a two-year period and was subsequently forced to step down from these duties due to ill-health. Ela remained at the Abbey until her death in 1261.

On her tombstone in Lacock is the Latin inscription: ‘Below lie buried the bones of the venerable Ela, who gave this sacred house as a home for the nuns. She also had lived here as holy abbess and Countess of Salisbury, full of good work’. Ela clearly made a significant contribution to the development of notable institutions in Wiltshire.

Research by Nicola MacDonald-Dodin, edits and notes by S. Ali

Notes

1 More about this topic can be found at the following link: https://www.bl.uk/the-middle-ages/articles/women-in-medieval-society#

2 The Crusades were a series of religious wars between Christians and Muslims during the 11th, 12th and 13th centuries. The Institute of Historical Research has a specific collection relating to the Crusades which can be accessed at the following link: https://www.history.ac.uk/library/collections/crusades-history

3Within the feudal system in Medieval England, if a young heir of a lord became a royal ward, this means that the King or Queen had legal guardianship of them until they came of age. The King had certain wardship rights over them, such as specific rights in relation to the land/property the ward had inherited, as well as control over who they would marry. Further explanation about wardship can be found at the following source (Mapping the Medieval Countryside: The feudal system and the royal prerogative): http://www.inquisitionspostmortem.ac.uk/the-feudal-system-and-the-royal-prerogative/

4The once-thriving town of Old Sarum has a hill fort and a royal castle, and dates back to the Iron Age. During the medieval period, Richard Poore, the bishop of Sarum from 1215, and the clergy living there disliked the location of Sarum on a hilltop due to the cold and windy weather which made life difficult, and it was also clear that the relationships between the military and the clergy were deteriorating. Poore sought permission from the Pope to have a new cathedral built outside of the city. In 1220, permission was granted and Poore oversaw the building of new city in its current location in the flood plain of three rivers. The foundation stones for the new cathedral were laid by William Longespee and Ela, Countess of Salisbury. Following this, the old cathedral was demolished and the stones were moved to be used at the new cathedral at Salisbury. You can find out more about Old Sarum at the English Heritage website: https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/old-sarum/

For another link to Old Sarum, look out for our profile on Eleanor of Aquitaine.

5The Magna Carta is a royal charter of rights and is one of the most famous documents in the world. It established that nobody (including the king) was above the law, and specified that everyone has a right to justice and a fair trial. This has left a tremendous legacy and has set the precedent for the rights we have today: many of the principles of the Magna Carta are included in documents we use today such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). You can read more about the Magna Carta at the British Library’s website: https://www.bl.uk/magna-carta/articles/magna-carta-an-introduction

Although the Magna Carta rarely mentions women, and often only in relation to their relationships to men (e.g. as heiresses or widows), it did have a clause stating that widows could have their inheritance and were not obliged to remarry (if they preferred to live without a husband). Although the mention of women in the Magna Carta has been debated at length by historians and scholars, it is certain that it left a legacy for the future of women’s rights and was used by the later Women’s suffrage movement.

Salisbury Cathedral’s Magna Carta can be viewed by the public in its permanent exhibition at Salisbury Cathedral (when it is open to visitors).

6 Hinton Priory was a new site in Somerset – the original Priory of Carthusians had been established by her husband at Hatherop in Gloucestershire in 1222. Further information about Hinton Priory can be found at the Hinton Charterhouse website (listed in the sources).

Sources

Hinton Charterhouse, n.d., Priory history. http://www.hintoncharterhouse.com/priory.htm

McConnell, A., 2015, Life of Ela, Countess of Salisbury. Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre. https://wshc.org.uk/blog/item/the-life-of-ela-countess-of-salisbury.html

Order of Medieval Women, n.d., Ela, Countess of Salisbury. https://www.medievalwomen.org/ela-countess-of-salisbury.html

Robinson, Sue, 2020, Ela, Countess of Salisbury http://www.chitterne.com/history/index.html

Victoria County History, 1911, Houses of Carthusian monks: the priory of Hinton. A history of the country of Somerset: Volume 2, ed William Page. British History Online. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol2/pp118-123#anchorn4