Jill Furse, Actress 1915 -1944

“Sunlight seen through April showers”

Jill Furse was a young actress of rare talent who enjoyed brief success in the late 1930s. Thwarted by both ill health and the Second World War, she was nevertheless determined to live a full and joyful life and is remembered as much for her effect on others as for her acting credits.

Jill was born in Salisbury2 at Netherhampton House, and spent a great deal of her childhood there. The house was the home of her grandfather, the poet, Sir Henry Newbolt. Edith Olivier3 was a family friend, and as a young woman Jill spent time with her in convalescence at the Daye House in Wilton. Edith thought her ‘very intelligent, sensitive, and great fun’.4 Salisbury was Jill’s favourite city and it served as a crossing point throughout her life. Jill was drawn naturally to the theatre and trained in drama before making her debut in 1935, playing the heroine, Francine, in National 6 at the Gate Theatre, Villiers Street, London.5,6. Further theatre parts and radio broadcasts followed, including a reprisal of National 6 for radio in 1937.

She was a dedicated and sensitive actress, considered to have a rare gift, but frequent bouts of illness,7 suffered from childhood, lost her some coveted roles, including the Shakespearean heroines at the Old Vic (to be produced by John Gielgud). Her ‘year of success’ spanned 1938 and 1939, when she starred in Goodness, How Sad by Robert Morley at the Vaudeville Theatre.8 The show was a huge hit, described as ‘the most delightful play in London’,9 and was also broadcast on national television10,11 . Jill also starred in The Intruder (translated from François Mauriac’s Asmodée), at Wyndham’s Theatre, produced by Norman Marshall – a finely written, much more serious play – in which she was acclaimed as ‘extraordinarily moving and tender’.) In addition there were film roles in Goodbye Mr Chips and There Ain’t No Justice.

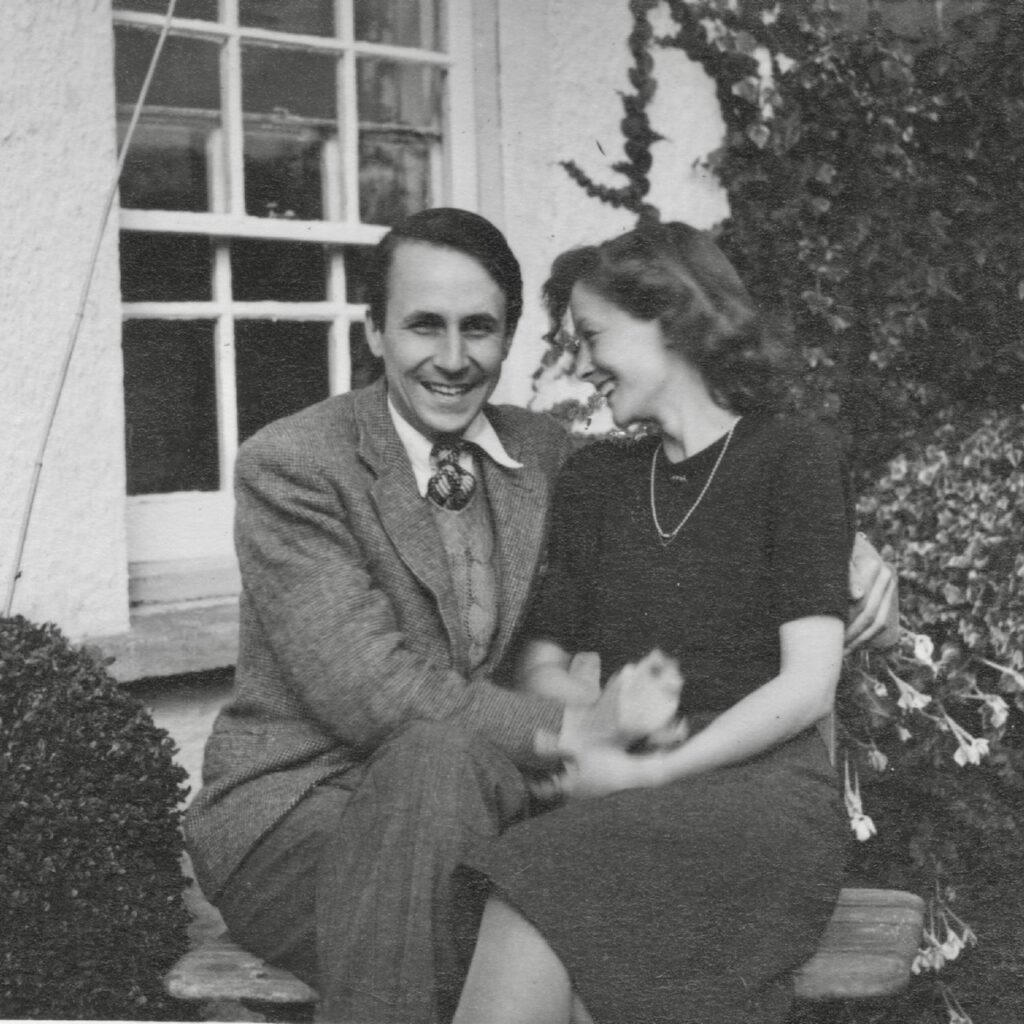

In 1937 Edith Olivier had invited Jill for a visit to introduce her to Laurence Whistler12, the younger brother of Rex13,14. It was a little time before Jill decided definitely in Laurence’s favour, but they eventually fell deeply in love. Laurence was making little money from his writing and engraving but Jill was quite prepared for them to live on her earnings as an actress. In September 1939, with most London theatres closed at the outbreak of war15, they obtained a special license and married quietly at Salisbury Cathedral with only a handful of guests,16 including Edith Olivier, Siegfried Sassoon and Lord David Cecil. The reception afterwards was held at The Walton Canonry in the Close which Rex had leased for his parents. After a honeymoon in Devon, they returned to the Close for Christmas, and stayed for three months.

With very little money, the young couple then moved into a cottage on the Furse family estate, Halsdon in Devon, rejoicing in the simplicity of a home in a beautiful valley with no electricity, indoor plumbing, or running water. Jill learned to cook and tackled new recipes with gusto and talent, Laurence engraved glass, and they both wrote poetry. After Laurence was called up to join the army, they only met again during his leaves – a few short intensely happy days at a time (they called them ‘lives’) in Devon, the Daye House, or in hotels around the country. Their first child Simon was born in Devon in September 1940 under threat of invasion; Laurence recording that Jill and her mother had buried their jewellery in the garden while the woefully ill-equipped Home Guard prepared to defend the bridges. 17

Despite recurring bouts of joint pain, sinus headaches, and exhaustion, Jill longed to be back in the theatre, and for a short period in 1942 she was again a great success as the lead in Rebecca at the Strand Theatre; ‘a lost, scared girl painfully finding herself, simply and sensitively, an altogether lovely performance’.18, 19 However, her health crashed, forcing her to pull out after four weeks. As she travelled back to Devon through Salisbury station, Laurence (then stationed at Tidworth) managed to see her for a few brief moments and provide sugar and eggs for her sustenance.20 Jill continued to have cycles of ill health but travelled to be with Laurence in between. Meanwhile she again attempted to resume her career, both as an artistic calling and because of the practical need to pay her substantial doctors’ bills. She accepted another part in a play in 1944 (Kate O’Brien’s The Last of Summer, produced by John Gielgud) only to have to pull out again before the dress rehearsal on discovering that she was pregnant. When the play eventually went on without her it lasted only two weeks as London again came under heavy bombing.21 Jill gave birth to her daughter Robin in Devon that November with a great sense of achievement, amongst the backdrop of her health concerns, money worries and fears about the war.22 However, doctors were slow to notice a decline in her health and she sadly died twelve days after the birth, aged just 29 years old.23

After the war Laurence privately published a limited run of her poems24, JILL FURSE her Nature and her Poems, copies of which he and other family members gave as gifts to friends. Laurence married Theresa, Jill’s younger sister, in 1950. In 1964 he published The Initials in the Heart – the story of his marriage to Jill. He followed it in 1967 with To Celebrate Her Living, a collection of 70 poems written to Jill’s memory. Together with her poems these two books denote Jill’s lasting legacy in the effect she had on those around her.

Written and researched by Janet Thirkell. Edits by S.Ali.

We would like to extend our thanks to Robin Ravilious for providing additional information, insights and photographs, and for comments on a previous version of this profile.

Notes

1The Times Archive, 10, 13 Mar 1939 [online] (accessed 12 Jan 2021)

2 Born Barbara Dolignon Furse on 3 Apr 1915; Find a Grave via ancestry (via WSHC) lists birth and death dates (accessed 19/11/20). A birth announcement appeared in The Times on 6 April 1915, The Times Archive, 1, (accessed 12 Jan 2021)

3 Edith Olivier was a writer and a well-known society hostess. [Her story will also be published on the Her Salisbury Story website.]

4 Whistler, Laurence, 1964, The Initials in the Heart, John Murray, London, 7

5The Times Archive ‘Gate Theatre Studio ‘National 6’’, 12, 30 Oct 1935 [online] (accessed 12 Jan 2021)

6 The Gate Theatre in Villiers Street was an independent club theatre which closed in 1940. By operating as a members only club it was able to avoid the Lord Chamberlain’s censorship.

7 Thought to have been Lupus: Whistler, Laurence, 1964, The Initials in the Heart, John Murray, London, 236

8 Whistler, 1964, 45

9 The Times Archive, 10, 6 Feb 1939 [online] (accessed 12 Jan2021)

10Goodness, How Sad was a bit of a family affair as Judith Furse had a smaller part and Roger Furse designed the scenery. These two were brother and sister and their father was a first cousin of Ralph Furse, Jill’s father. [The Times Archive, 10 3Oct 1938]

11 By September 1939 there were only 20,000 television owners, all in London (Imperial War Museum website https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/the-nation-at-a-standstill-shutdown-in-the-second-world-war (accessed 3 May 2021)

12 Laurence Whistler was a poet, writer and glass engraver. His glass prism (1985) – a memorial to his brother, Rex, may be seen in Salisbury Cathedral.

13 Rex Whistler was a celebrated painter, designer and illustrator and part of the fashionable society set. He was killed in action in 1944. He was a close friend of Edith Olivier’s and some of his paintings, featuring Edith may be seen in Salisbury Museum, which also holds the Rex Whistler archive: https://salisburymuseum.org.uk/collections/rex-whistler-archive

14 Whistler, 1964, 7

15 ‘There were 24 plays and musicals on in the West End on 7 September 1940 at the start of the Blitz; one week later only two theatres were open.’ (Imperial War Museum website https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/the-nation-at-a-standstill-shutdown-in-the-second-world-war (accessed 3 May 2021)

16 From The Times Archive, 11, 9 Sept 1939 (accessed 12 Jan 2021):

‘MR. L WHISTLER AND Miss FURSE A marriage has been arranged, and will take place immediately in Salisbury Cathedral, between Laurence, younger son of Mr. Henry Whistler and Mrs. Whistler, of The Close, Salisbury, and Jill, eldest daughter of Major R. D. Furse, C.M.G., D.S.O. and Mrs. Furse. of 18, Lansdowne Walk, W.ll.’

17The Times Archive, ‘Births’, 1, 10th Sept 1940 [online] (accessed 12 Jan 2021); Whistler, 1964, 82-3. Simon Whistler, like his father, became an engraver and artist; Simon and Laurence often worked together on commissions. Simon was also a musician, playing the viola in orchestras. He had a career lasting 30 years. Simon died in 2005.

18 The Times Archive, ‘The Theatres Three Productions in London’, 8, 19 May 1942 [online] (accessed 27 Feb 2021)

19The Times Archive, 6, 22 May 1942 [online] (accessed 27 Feb 2021)

20 Whistler, 1964, 129

21 Whistler, 1964, 203

22 Whistler, 1964, 228. Jill’s daughter, born in 1944, is the writer and illustrator Robin Ravilious.

23Find a Grave via WSHC website lists birth and death dates. (accessed 19/11/20). Jill Furse is buried at the south edge of Dolton churchyard (St Edmund’s) in Devon – an Irish yew marks the grave.

24 Jill Furse, her Nature and her Poems 1915-1944 selected poems with a biographical essay by Laurence Whistler: “London: (printed for Laurence Whistler by) The Chiswick Press (1945)” 150 copies pub. Jul 1945, another 100 in Dec 1945. https://www.abebooks.co.uk/servlet/BookDetailsPL?bi=22921438638&searchurl=kn%3Djill%2Bfurse%26sortby%3D17&cm_sp=snippet-_-srp2-_-title13

Further Reading

Whistler, Laurence, 1945, Jill Furse, her Nature and her Poems 1915-1944 selected poems with a biographical essay by Laurence Whistler, (printed for Laurence Whistler by) The Chiswick Press, London, [150 copies pub. Jul 1945, another 100 in Dec 1945]

Whistler, Laurence, 1964, The Initials in the Heart, John Murray, London